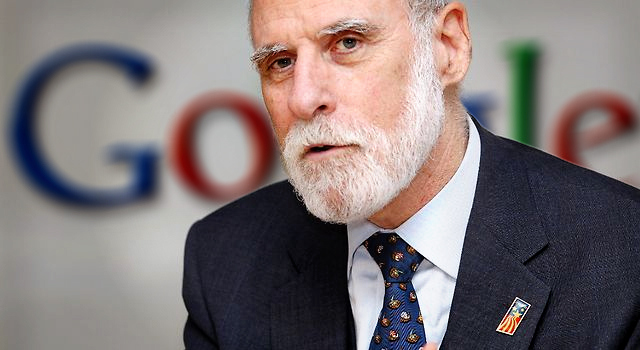

Google’s chief internet evangelist Vint Cerf is making headlines today after suggesting that “privacy may actually be an anomaly.” Speaking at a Federal Trade Commission event, the company vice-president said privacy is a relatively new invention, and that “the technology that we use today has far outraced our social intuition, our headlights. … [There's a] need to develop social conventions that are more respectful of people’s privacy. We are gonna live through situations where some people get embarrassed, some people end up going to jail, some other people have other problems as a consequence of some of these experiences.”

The knee-jerk reaction might be to write off Cerf’s comments because he works at Google, a company that is strongly interested in information being public rather than private, but the thought does actually warrant further consideration. For one thing, Cerf isn’t some corporate shill - as one of the “inventors” of the internet, he’s been a strong proponent of peoples’ rights on it. But more to the point, he’s right about privacy being a relatively new concept.

In my upcoming book Humans 3.0, I devote a chapter to how privacy is largely a technological by-product. The earliest people huddled together in caves and therefore had no expectations of it. Each successive technological invention that affected how people lived increased that expectation slightly, to the point where we now consider it an alienable right. But that hasn’t always been the case.

As Gregory Ferenstein notes over at TechCrunch, bathing and going to the bathroom were largely public acts for most of human history, with the notion of private rooms only becoming fashionable in the 19th century. The advent of heating and electricity in the home finally allowed families to split up within their domiciles, since they no longer needed to rely on each other for warmth.

When the telephone came along, it was first deployed as a sort of shared utility. Up until the Second World War, party lines - where several houses would share the same line - were common. Each house might have had a special ring to indicate calls destined for its inhabitants, but otherwise people were free to eavesdrop on each other’s calls.

As Cerf mentioned, the notion of privacy is still quite different in smaller towns today, like the one he used to live in. “In a town of 3,000 people there is no privacy. Everybody knows what everybody is doing.”

Privacy didn’t get legal protections until the 20th century, as a reaction to continuing technological advances such as photography and the advent of mass media. It wasn’t till the landmark 1967 case of Katz v. the United States that the right to privacy was recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Further complicating the issue today is the fact that there is no one definition of privacy. As a subject that encompasses social mores, demographics, psychology, law and technology, it’s a complex topic that few scholars and experts can agree on. As Canadian privacy researcher Tracey Ann Kosa noted in her paper on measuring privacy (links to PDF), “The significant difference in approach indicates that agreement on the theory of privacy is a long way off.”

As Kosa suggested when I spoke with her earlier this year, it might be time to form a sort of multi-disciplinary Manhattan Project-like effort to fully study and understand the human notion of privacy - as varied as it is - before our law makers take actions on it. That seems to be the point of Cerf’s comments. As he said, “This is something we’re gonna have to live through. I don’t think it’s easy to dictate this.”

Marc Venot

November 22, 2013 at 12:36 am

You can say it’s a bourgeois attitude. If it’s grand that’s great but it’s petit not.

Blaise Alleyne

December 2, 2013 at 1:32 pm

“The earliest people huddled together in caves and therefore had no expectations of [privacy]. Each successive technological invention that affected how people lived increased that expectation slightly, to the point where we now consider it an alienable right. But that hasn’t always been the case.”

Um, couldn’t you say that about almost any right we consider an inalienable today? Maybe some came about through social innovations (e.g. governance, enforcability, rule of law), whereas others may have had more to do with technological innovations.

But of which inalienable rights did people huddled together in caves have any expectation?