AT&T takeover highlights Canadian carrier vulnerability

If you’re interested in innovation and the competition that enables it, you’ve probably been following the saga that is AT&T’s proposed takeover of T-Mobile in the United States. If you haven’t been paying attention, you should because it’s a deal that - if it were to go through - would have big direct implications on technological advancement in the United States and indirect effects elsewhere, especially here in Canada.

To summarize, AT&T (the second-largest U.S. wireless provider, next to Verizon) earlier this year offered $39 billion to take over T-Mobile, the fourth-largest (Sprint is third). The deal would make AT&T the biggest U.S. cell company, with 130 million subscribers.

To summarize, AT&T (the second-largest U.S. wireless provider, next to Verizon) earlier this year offered $39 billion to take over T-Mobile, the fourth-largest (Sprint is third). The deal would make AT&T the biggest U.S. cell company, with 130 million subscribers.

When the announcement was initially made in March, the only logical reaction - from a Canadian standpoint - was, duh, there’s no way it’ll ever be allowed to happen. After all, the Canadian government had just recently decided that three national wireless carriers was not enough to drive competition on innovation and pricing, so it went ahead and bent the law to get more players into the market. How would the United States, with a population 10 times the size of Canada’s, make do with only three national carriers? Anyone with half a brain could see that, despite AT&T’s rhetoric to the contrary, such a deal would be nothing but bad news for consumers.

A few weeks ago, the Department of Justice voiced that illogic when it sued to kill the deal on anti-trust grounds. “We feel the combination of AT&T and T-Mobile would result in tens of millions of consumers across the U.S. facing higher prices, fewer choices, and lower quality products for wireless services,” said deputy attorney general James Cole. Again, from the Canadian perspective, no duh.

Where the proposed deal goes from here is anyone’s guess, but if the DOJ has any weight - and it does - then the Vegas odds on it going through are looking pretty low.

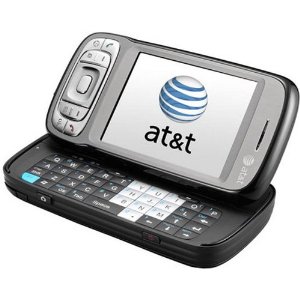

Where things get interesting for Canadians is that T-Mobile uses the same frequency of airwaves, known as Advanced Wireless Spectrum, as most of the new carriers that have sprung up to compete against Bell, Rogers and Telus. Those new cellphone providers - Videotron, Mobilicity, Wind Mobile and Public Mobile - are all tiny, insignificant minnows to the giant global cellphone makers, so they must piggy-back on T-Mobile for devices. The U.S. provider, which has 34 million customers (more than the entire population of Canada) is almost like a big brother, with the new Canadian carriers getting its hand-me-downs.

AT&T has said it plans to repurpose T-Mobile’s AWS spectrum for fourth-generation (4G) long-term evolution (LTE) smartphones, which means customers of the smaller provider might have to switch to new phones. If the deal did go through, that could have a similar pull effect on the new Canadian carriers, who might then be forced to upgrade to LTE or risk having even fewer phones to offer customers than they do now. While the small guys aren’t disclosing their financials, it’s probably safe to say they don’t have a whole lot of money to spend on such costly technology upgrades.

Spectrum is an incredibly complicated and - let’s face it - boring topic. What this situation does highlight, though, is just how precarious the existence of Canada’s new wireless carriers is. Their fates are currently tied to one particular flavour of spectrum and, in essence, one particular U.S. carrier. If anything should happen to that carrier or its spectrum, they face the real possibility of ceasing to exist.

As such, it’s clear what the Canadian government must do in the next spectrum auction, expected next year. It once again needs to reserve a portion of licenses, known as a set-aside, for the newer companies in order to give them a chance at existing. Just as Bell, Rogers and Telus would have paid anything in the previous auction - if there were no set-aside - to keep new players out, so too will they break the bank in the next one to keep the newcomers on that single-spectrum precipice.

It may not be the pure market solution our government says it likes, but this is a situation of their own creation. As the cliche goes, they’ve made their bed so now they must lie in it.

Short memory here. Rogers buying Fido. Anybody remember? It just went through…. in 2005

Maybe you should write an article about the airwaves opened by the switch to digital (numeric) (for example which bands are the best)?

For the customer it’s not a problem to buy new smartphones since this is a new technology not already mature with large improvement with every generation. Also it brings a lot of dough in the government coffers. Those micros providers have still to show that their offer are better than the big ones (or why they can’t).

In France Numericable has just made a social offer for 4 euros providing a 2 Mbit/s internet connection, the TNT and a phone line only to receive calls and emergency numbers (http://www.01net.com/editorial/540422/numericable-lance-une-offre-d-acces-a-linternet-social-a-4-euros/)

There is another side. AT&T’s power has allowed it to get certain manufacturers to NOT produce models that work in 1700. (iPhone being a good example). This is to prevent T-Mobile from competing against AT&T. And it has prevented the smaller guys in Canada from competing against the big guys.

Note that neither Bell/Telus nor Rogers have deployed 1700 on their network despite having bought spectrum at great price. One likely reason is that they wouldn’t want popular phone to be produced at 1700 since their new competitors would then have the popular phones.

That’s where they should be force to relinquish spectrum if they don’t use it.